Owing to the incessant advertising from calcium supplements-manufacturing companies, the elderly are often encouraged and coaxed into self-prescribing calcium supplements, in the belief that calcium supplements are good for their health. Traditionally, supplemental calcium has been claimed to be effective for the prevention and management of osteoporosis and fractures. Over the last couple of decades, the prescription and use of calcium supplementation has risen sharply (Tankeu et al. 2017). But is there any proof that calcium supplements work? And, is this exponential rise in the use of calcium pills warranted?

Owing to the incessant advertising from calcium supplements-manufacturing companies, the elderly are often encouraged and coaxed into self-prescribing calcium supplements, in the belief that calcium supplements are good for their health. Traditionally, supplemental calcium has been claimed to be effective for the prevention and management of osteoporosis and fractures. Over the last couple of decades, the prescription and use of calcium supplementation has risen sharply (Tankeu et al. 2017). But is there any proof that calcium supplements work? And, is this exponential rise in the use of calcium pills warranted?

Let us dig a little deeper to know the truth.

LACK OF EVIDENCE FOR EFFECTIVENESS OF CALCIUM PILLS

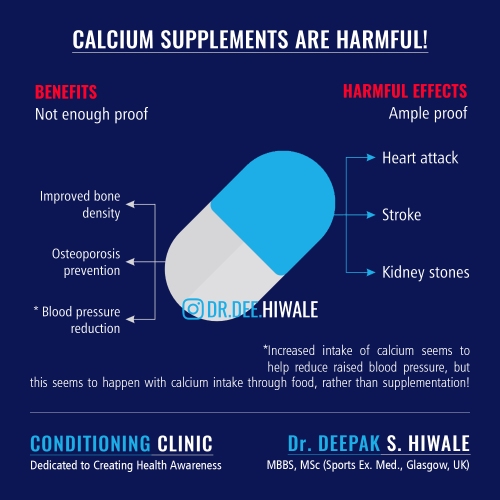

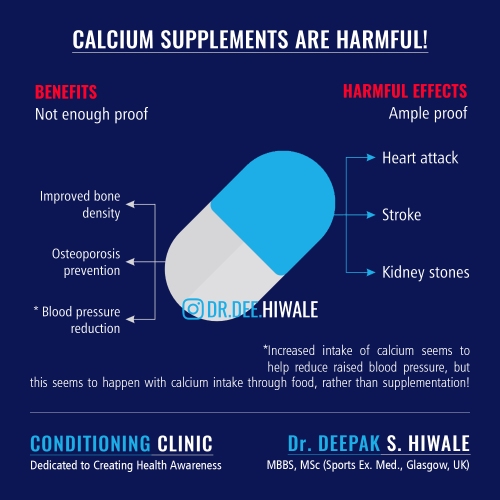

A cursory look at the literature immediately throws up the lack of conclusive evidence for the effectiveness of calcium supplements. As if that weren’t enough, use of calcium supplements seem to be strongly associated with cardiovascular events and the risk of death due to cardiovascular or other causes.

The rationale of prescribing calcium supplements, for whatever purpose, especially in the elderly population (already at risk of cardiovascular disease), therefore seems to be quite questionable.

CALCIUM FOR OSTEOPOROSIS AND REDUCED BONE MINERAL DENSITY

Although there is consensus that calcium intake is crucial for bone health and other physiological functions, the source of calcium intake and quantity remains controversial. While increasing calcium intake through food is both beneficial and safe, acquiring calcium through supplements and pills seems to be neither beneficial nor safe!

It is a popular belief, amongst doctors and lay people, that calcium supplementation is crucial for prevention of osteoporosis – especially, in the elderly in the absence of adequate dietary intake. However, scientific evidence in support of such a ‘belief’ is flimsy, to say the least.

It is a popular belief, amongst doctors and lay people, that calcium supplementation is crucial for prevention of osteoporosis – especially, in the elderly in the absence of adequate dietary intake. However, scientific evidence in support of such a ‘belief’ is flimsy, to say the least.

The NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis and Therapy said in 2001 that ‘adequate calcium and vitamin D intake is crucial to develop optimal peak bone mass and to preserve bone mass throughout life, supplementation (with these 2 nutrients) may be NECESSARY in persons not achieving dietary intake’ (NIH 2001). However, this was later challenged by meta-analysis studies which reported results to the contrary – calcium supplementation did not provide any benefit for hip or lumbar bone mineral density and therefore, did not translate into reduced lumbar or hip fracture risk (Bolland et al. 2008; Anderson et al. 2016).

The authors of a meta-analysis study of prospective cohort studies and randomized-controlled trials concluded quite emphatically that calcium supplementation was not beneficial for reduction of fracture risk (Bischoff-ferrari et al. 2007).

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTATION

A major health concern of calcium supplementation is the associated cardiovascular disease (CVD) risks; ‘a rising body of evidence’ seems to suggest just such a strong association (Tankeu et al. 2017). Calcium supplementation induced progression of atherosclerosis is often suspected as underlying the association between calcium intake and CVD risk (Anderson et al. 2016).

Calcium supplementation – especially in high doses – may increase the risk of non-skeletal adverse effects: cardiovascular and other (Bolland et al. 2013; Anderson et al. 2016; Favus 2011):

- Atherosclerosis (formation of atheromatous plagues within arteries),

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack),

- Stroke (paralysis), and

- Non-cardiovascular adverse effects like development of renal calculi (kidney stones)

Calcium supplementation also increases the risk of all-cause mortality (early death due to any reason) (Anderson et al. 2016; Bolland et al. 2013; Michaelsson et al. 2013)! A Swedish study concluded that ‘high intake of calcium is women are associated with higher death rates from all causes and cardiovascular disease’(Michaelsson et al. 2013). Calcium supplements increased heart attack risk by 31%, risk of stroke by 20% and all cause-mortality by 9%, reported a large meta-analysis study of 12,000 patients (Bolland et al. 2010)!

There is ‘consistent evidence from 13 randomised placebo controlled trials involving about 29,000 participants and about 14,000 incident cases of myocardial infractions and strokes’ that calcium supplements (either take alone or in combination with vitamin D) do increase the risk of cardiovascular risks (Bolland et al. 2011).

CALCIUM AND BLOOD PRESSURE REDUCTION

Several studies have demonstrated a direct – almost causal relationship – between calcium intake and BP reduction (Dickinson et al. 2006; Cormick et al. 2015). Calcium supplementation has also been shown to be of benefit in pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH), especially pre-eclampsia (Higgins & Green S 2011).

No one knows why and how calcium intake reduces blood pressure (BP). However, almost everyone agrees that since calcium intake affects vitamin D and parathyroid hormones levels. Low levels of calcium intake may lead to increased compensatory release of vitamin D and parathyroid hormone. Increased vitamin D and parathyroid hormone, in turn, increase reactivity of vascular smooth muscle (muscle of the arteries) which raises peripheral resistance and therefore, BP (Cormick et al. 2015; Paziana & Pazianas 2015; Webb 2003).

Raised BP, therefore, seems to be an indirect effect of low calcium levels (owing to low intake) in an individual (Tankeu et al. 2017; Heaney 2006).

Having said that, the above remains a hypothesis and has not been proven conclusively (Tankeu et al. 2017).

CALCIUM FROM FOODS IS ‘CARDIO-PROTECTIVE’

Although much of the literature agrees that calcium intake is crucial for bone health and other physiological functions, the source of calcium intake and quantity remains controversial. While calcium supplementation increases the risk of cardiovascular and other adverse effects, dietary calcium intake (through foods) seems to be safe (Xiao et al. 2013; Bolland et al. 2013).

Researchers are of the opinion that people who partake higher doses of calcium supplements to make up for the daily requirement of calcium, are at the greatest risk of coronary atherosclerosis than the ones that get much of their calcium from food sources. On the other hand, those who increase calcium intake through ingestion of calcium-rich foods exhibit a decreased risk of atherosclerosis and therefore, heart attacks or strokes (Anderson et al. 2016).

As opposed to calcium-rich foods, calcium supplements increase the risk of incident CAC (coronary artery calcification, a measure of calcium content in the coronary arteries – higher the CAC score, higher the risk of a heart attack). Also, it is often suggested that calcium supplementation causes a more rapid rise in serum calcium levels, which causes a hypercoagulable state (blood thickens and is more likely to coagulate and contribute to plague formation) (Leifsson & Ahren 1996). This hypercoagulable state increases the risk of cardiovascular mortality (Reid et al. 2011).

MORE IS NOT BETTER, IT IS WORSE

As if calcium supplementation itself wasn’t bad enough, many people resort to taking high doses of calcium supplements. A tablet of calcium typically contains 500 to 650mg of calcium. Typically, users resort to popping in a couple of pills or more, thinking ‘more is better’. This is not only wrong but harmful because higher doses increase the health risks.

In a large study of 60,000 plus Swedish women, who were followed up for a median 19 years, it was found that women who took higher doses (1400mg/day and above) – compared to those who stuck to 600-1000 mg/day were associated with higher rates of cardiovascular diseases and death from all causes (Michaelsson et al. 2013). Another group of researchers reported increased risk of cardiovascular events with a dose of more than 800mg/day (Bolland et al. 2010). Chung et al. have also challenged the ‘more is better’ strategy of calcium supplementation; their study found that a dose of more than 1000 mg/day did elevate the risk for CVD and CVD mortality. The equivalent risk-elevating dose for men was found to be 1500mg/day (Chung et al. 2016).

Taking such grave cardiovascular and mortality risks into consideration, Bolland et al. were of the opinion that any benefits of low-dose calcium supplements for bone health are far outweighed by the high cardiovascular risks (Bolland et al. 2008).

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

Currently, there’s very little evidence that calcium supplementation, especially over and above the daily recommended allowances, is beneficial for osteoporosis or fracture risk. Given that calcium supplementation does not do what it is supposed to be doing but, on the contrary, increases health risks, the argument in favour of taking calcium pills, at this point in time – for whatever reason – is not a very strong one.

Blanket prescribing (by doctors) of calcium supplements for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and reduction of fracture risks, especially in the elderly (already) at risk of cardiovascular events, should therefore be STRONGLY DISCOURAGED.

If you indulge in self-prescription of calcium supplements, you need to be wary of the adverse effects.

Calcium-rich foods are an effective and a safe way to increase calcium intake and should always be preferred over calcium supplements.

IN A NUTSHELL

- Calcium supplements are both useless and harmful, especially in high doses

- Any benefits of low-dose calcium supplements for bone health are far outweighed by the high cardiovascular risks

- Calcium from food sources is both beneficial and harmless

PLEASE FEEL FREE TO DISCUSS WITH YOUR DOCTOR, THE CARDIOVASCULAR RISKS, IF YOU ARE PRESCRIBED CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTS!

REFERENCES

Anderson, J.J.B. et al., 2016. Calcium intake from diet and supplements and the risk of coronary artery calcification and its progression among older adults: 10-year follow-up of the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Journal of the American Heart Association, 5(10), pp.1–14.

Bischoff-ferrari, H.A. et al., 2007. Calcium intake and hip fracture risk in men and women : a meta- analysis of prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled. , pp.1780–1790.

Bolland, M.J., Grey, A. & Reid, I.R., 2013. Calcium supplements and cardiovascular risk: 5 years on. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 4(5), pp.199–210. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2042098613499790.

Bolland, M.J. et al., 2010. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. Bmj, 341(jul29 1), pp.c3691–c3691. Available at: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.c3691.

Bolland, M.J. et al., 2008. Vascular events in healthy older women receiving calcium supplementation: randomised controlled trial. Bmj, 336(7638), pp.262–266. Available at: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.39440.525752.BE.

Bolland, M.J. et al., 2011. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. Bmj, 342(apr19 1), pp.d2040–d2040. Available at: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.d2040.

Chung, M. et al., 2016. Calcium intake and cardiovascular disease risk: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165(12), pp.856–866.

Collaboration, T.C., Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: Protocols. In Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Cormick, G. et al., 2015. Calcium supplementation for prevention of primary hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (6). Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010037.pub2/abstract.

Dickinson, H.O. et al., 2006. Calcium supplementation for the management of primary hypertension in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (1469–493X (Electronic)), p.CD004639.

Favus, M.J., 2011. The risk of kidney stone formation : the form of calcium matters 1 – 3. Am J Clin Nutr, 94, pp.5–6.

Heaney, R.P., 2006. Calcium intake and disease prevention TT – Ingesta de cálcio e prevenção de doença. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol, 50(4), pp.685–693. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0004-27302006000400014.

Higgins, J. & Green S, (editors), 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Available at: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Leifsson, B.G. & Ahren, B., 1996. Serum calcium and survival in a large health screening program. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 81(6), pp.2149–2153. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8964843.

Michaelsson, K. et al., 2013. Long term calcium intake and rates of all cause and cardiovascular mortality: community based prospective longitudinal cohort study. Bmj, 346(feb12 4), pp.f228–f228. Available at: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.f228.

NIH, 2001. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA, 285, pp.785–795.

Paziana, K. & Pazianas, M., 2015. Calcium supplements controversy in osteoporosis: a physiological mechanism supporting cardiovascular adverse effects. Endocrine, 48(3), pp.776–778.

Reid, I.R. et al., 2011. Cardiovascular effects of calcium supplementation. Osteoporos Int, 22(6), pp.1649–1658.

Tankeu, A.T., Ndip Agbor, V. & Noubiap, J.J., 2017. Calcium supplementation and cardiovascular risk: A rising concern. Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 19(6), pp.640–646.

Webb, R.C., 2003. Smooth muscle contraction and relaxation. Advances in physiology education, 27(1–4), pp.201–6. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14627618.

Xiao, Q. et al., 2013. Dietary and supplemental calcium intake and cardiovascular disease mortality: the National Institutes of Health-AARP diet and health study. JAMA internal medicine, 173(8), pp.639–46. Available at: /pmc/articles/PMC3756477/?report=abstract.

Read Full Post »

You must be logged in to post a comment.